Capacity market for Kazakhstan – to keep lights on at the least cost.

- alexeypresnov

- 16 дек. 2023 г.

- 9 мин. чтения

Last time we focused on the fact that Kazakhstan needs a completely different power market than the currently functioning system of individual contracts for investment projects and additional payments for existing generation. Real incentives are needed for resource competition in all segments, including the capacity market, and that is why it must be designed in a clear linkage with the design of the electricity market. Centralized (market wide) capacity mechanisms initially came to Europe from the USA, where in several jurisdictions they were created in addition to centralized electricity markets, the so-called. gross pools, the main segments of which are the day ahead market and the real time market.

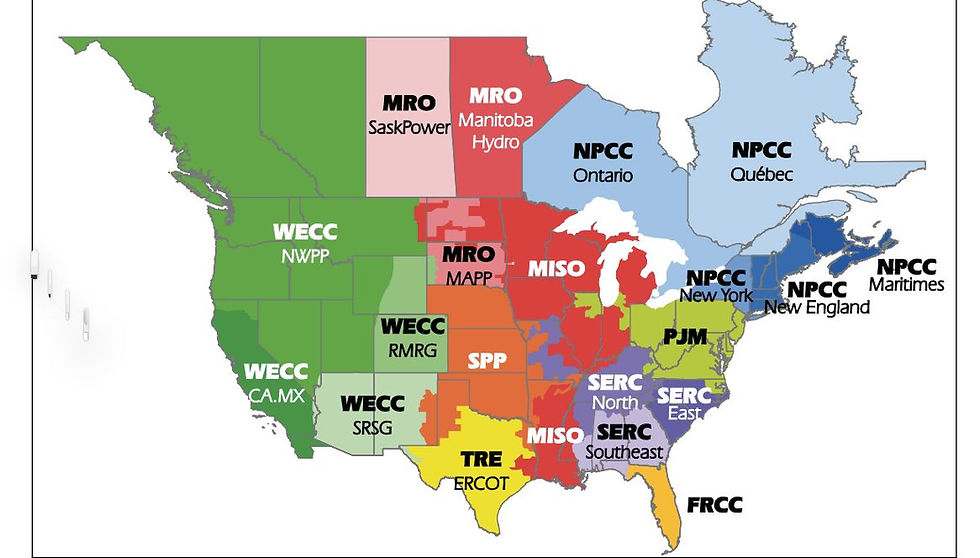

Russia copied approximately the same model, with some simplifications and additions, from America at the beginning of the 2000s, and the wholesale electricity market there had become mandatory for all generation facilities with a capacity above 25 MW, in contrast to America, where market subjects themselves decide whether they need to participate in a centralized pool, organized as a non-profit organization of all participants, managing both the market and its physical infrastructure - backbone networks. But participation in PJM, ISO New England, ISO NY, CAISO, MISO or ERCOT is generally preferable and attractive for generation for a plenty of reasons. And in those jurisdictions where power markets exist, generation mainly participates in them, observing the principle: if you receive payment for capacity, be so kind as to provide your resources to the electricity market and other related segments. The essence of this rule lies in the very meaning of the capacity market - ensuring balance reliability (and therefore operational security) in the energy system by placing its resources at the disposal of the System Operator to perform these tasks.

In Europe, the situation is somewhat different, as centralized exchanges initially had been predominately voluntary just complementing bilateral contracts, according to the net pool principle. Over time, however, these exchanges turned out to be so convenient that the roles of bilateral contracts and exchanges were reversed - now these contracts mainly complement the exchanges, hedging the risks of short-term transactions. For a long time, markets, or more precisely mechanisms for separate payment for capacity, in Europe were the exception rather than the rule, but due to the rapid development of renewable energy sources since the beginning of the 1990s, the situation has changed. In many European countries from Britain to Poland, separate capacity payment mechanisms are used in one form or another precisely in order to provide confidence to System Operators in their ability to maintain sufficient reliability in power systems in the face of changing technologies and an accelerated Energy Transition by available resources specifically selected for these purposes.

CO resources must meet the requirements for the energy systems of today, when technological processes in energy supply are becoming more complex and volatile, when energy flows not only from generation to consumers through bulk grid and distribution networks, but also at the level of distribution networks due to local generation, when significant volumes of resources located behind the meter, combined into virtual power plants (VPP) managed by IT, when flexible generation is in a much greater demand than before to balance intermittent renewable energy sources. And therefore, the capacity market, together with other segments, must be modeled so that all these requirements and criteria make it possible to objectively, in a competitive process, select exactly those resources that the system needs, choosing the best ones. This is not an easy task, and very few countries with centralized capacity markets are able to cope with it.

For example, Russia, close to us, which seems to have gone through all the stages of reforms, has built a competitive market, a centralized one, according to American patterns - with a separate segment of power, in general, did not cope with this task. The power market in Russia today is strictly divided into an investment component and fixed costs payments to “old”, depreciated generation, and, as in Kazakhstan, is poorly connected with the electricity market segments from the resources’ overall competition point of view.

The basis of the investment process in the power market in Russia is the mechanism of CDAs – capacity delivery agreements, which are, in fact, hidden tariffs, a type of RAB methodology, where investments in energy facilities are paid back through long-term payments from consumers with a rate of return established by the regulator. The CDA mechanism, initially invented as an obligation of generating companies during privatization to build previously planned (largely according to Soviet plans) generation facilities, subsequently turned into a profitable and almost risk-free instrument of guaranteed return on investment for owners of electricity producing assets, becoming widespread in all investment projects, completely eliminating market mechanisms of competition between new (repowered) capacities and existing ones. The choice of such an investment mechanism is based on the postulate that with high inflation and, more broadly, high cost of capital, competition between new and old capacity is impossible in principle, since investments do not pay off in a reasonable time just due to a higher efficiency of the new capacity compared to the old one in the segments electricity market, as happens in other countries. And this is true - for example, an increase in the efficiency of power units compared to the industry average when implementing investment projects, say, by 15 or even 20% (CCGT plant versus steam power cycle) is not enough for savings from a reduction in variable costs for fuel, automation, and a reduction in fixed opex, etc. to pay off an expensive financing within a period acceptable to investors (10–15 years). It is even more so , if the price of fuel has been formed in a non-market way, if it’s subsidized in one way or another, diminishing the effect of saving, as is the case in Russia using regulated gas prices. This is the problem with all economies with high inflation and expensive capital - investments not only in energy in such countries are problematic and require special solutions.

But in competitive energy markets, this approach - separate prices for new and modernized capacity and existing “old” generation - breaks the organic connection between the market segments - electricity and capacity, since it undermines the basic principle of organizing such markets - simultaneous competition in all segments - short-term and long-term, which ultimately provides opportunities for comparison and selection of different technologies, ensuring an optimal generation structure through market based signals. It is also necessary to have in mind that in any markets there are always “special” projects that are implemented outside the markets, according to government decisions - usually these are nuclear power plants and large hydroelectric power plants, large renewable energy projects - and this already brings distortions into the competitive environment in addition to multiple prices for capacity market due to the use of mechanisms such as CDA, and thus almost completely destroys the competition there that ensures steady development. Competition remains just in the segment of old resources, where the depth of the market and its liquidity are initially low, augmented by conditional competition between investment projects “for the right to participate” - at the stage of selection according to quotas and parameters determined manually by officials.

And if we look again at how this is structured now in Russia, we will see that investment processes are mainly carried out on the basis of individual competitions for new generation (the so-called KOM NGO - competitive selection of capacity for new generating facilities), added by the ending program DPM - 1, as well as competitive capacity auctions based on quotas for repowered generation (DPM -2 or KOMMod, while the modernization criteria are not aimed at a significant increase in efficiency). To be fair, in COMMOD the overall efficiency of projects in all market segments is taken into account, but again without competition with old assets. As a result, multiple prices arise in the capacity market, paid by consumers to one or another generator under separate contracts, complemented by various “political” surcharges, distorting not only the competitive field, but also the very meaning of the capacity market, as a robust and transparent mechanism for the medium-term development of the energy system based on optimal costs.

As a result, all this, as with the usual monopoly model of the industry, leads to an oversupply of existing capacities, estimated on the Russian market at 20–40 GW and burdening the economy, since inefficient generation does not receive sufficient market signals for decommissioning. Moreover, this approach does not stimulate the technological efficiency of new projects - the lack of competition with old capacity makes it possible to plan new generation based on obsolete solutions, while price is of secondary importance, reliability at any cost comes first, not keeping lights at the least cost.

Considering this negative experience of Russia, in reforming the energy market of Kazakhstan, a different approach to organizing the capacity market is proposed, which allows us to mainly avoid the influence of country risk factors as well as the high cost of capital. We will not go into design details here, but the essence of the solution is to ignore these factors when forming a competitive market price for capacity at forward auctions for several years in advance, to remove them beyond the market perimeter, and to translate them into special add-ups calculated according to the benchmarks of “normal” and “country” cost of capital. This solution ensures both – direct competition between new and old resources, based on their profitability in all market segments and, thus, ensuring increased efficiency and development, and at the same time gives regulators an additional tool for price control in terms of protecting the market from sharp price surges. In other words, a single marginal price of power at extraction, calculated from the “normal” cost of capital for new and modernized generating facilities, allows them to “enter” the market at a relatively low bidden price, and due to higher efficiency in the electricity market, compete with less efficient ones, but with depreciated resources, gradually displacing the most expensive of them in maintenance and fuel consumption from the market. Prices in the capacity market are set only by new and modernized resources; they also receive multi-year contracts to pay for capacity at prices that comfort them to pay off projects. In this design, the old generation submits only price-taking bids and receives a single price for new (modernized) objects. In terms of fears that all power plants, including old ones, with this approach will receive a too high price, and this will increase the financial burden on consumers, the same logic applies as in the electricity market. If prices for generation are different (pay-as-bid), then we will end up with “inflated” bids that correspond to the expectations of market participants at the demand-closing price, but at the same time we will lose efficiency - inframarginal income for generation with the lowest capacity price they can afford, taking into account earnings in other segments.

Exactly this market model objectively stimulates the resources needed at a given time, provided that each segment is properly designed. For example, today Kazakhstan is in dire need of flexible resources. This means that the market design should be such that earnings on the intraday and balancing segments are high, but at the same time, the choice of specific technologies should also rely on other factors. In the presence of gas, open cycle gas turbines, combined cycle gas plants and gas reciprocal machines can ramp stably and frequently. These three technologies are in principle flexible but differ in efficiency and speed of load change. Gas engines are the fastest, but they have fairly high fixed maintenance costs, as well as relatively low power per unit. Gas turbines are slower, but more powerful, and with relatively high variable costs. CCGT units are fuel efficient, but not very fast and do not like transient conditions, especially the steam power part. And finally, there are batteries - the fastest, no fuel costs, but they are expensive in terms of capex, with limited power and effective operating time (capacity). Or, as an option, you can use the old generation somewhere for maneuvering, for example, on the intraday market. All these factors will have to be taken into consideration by generation operators when submitting bids on the capacity market, and as a result, the most efficient and needed by the market will be selected, based on its profitability in all segments.

Until the deficit observed today in Kazakhstan is eliminated, it is clear that both old and new generation will be in demand in the capacity market; the upper price cap for the total price of electricity and capacity will remain the price of imports from Russia. At certain times in the short-term electricity market, surges are possible, and prices may even exceed Russian import, especially in the South, due to grid congestions. To stop such surges and prevent excess income of the old generation during these hours, the so-called reliability options can be used on electricity market segments that directly link revenues in the capacity and electricity markets. Their essence is that when price exceeds a certain level on the electricity market set by the regulator - the strike price, they will not receive payments from consumers, these revenues will be returned to the market, which will reduce the overall price during times of scarcity in the system. New (modernized) resources will continue to earn money during these hours.

This is how, in general, in our opinion, the model of the wholesale electricity and capacity market in Kazakhstan should look like in a few years if the country wants to get out of the current crisis. But there are at least two more questions that must be answered while proposing a general design of the wholesale market before moving on to how tariff architecture and regulation should be restructured in the network complex and in the retail market - integral elements of a holistic approach to analysis and energy market modeling.

We are talking about renewable energy sources, through which the country will strive to achieve the goals and objectives set in the Strategy for Achieving Carbon Neutrality by 2060, and we are talking about heat supply, in particular thermal power plants, which Kazakhstan will find it very difficult to cope without in the next 20–30 years taking into account the climate of the country.

More about this in our next publications in this series.

Комментарии